The Canadians On Board The Titanic

/You’ll find them all over the country: reminders of the Canadians who were there on the night the Titanic struck the iceberg. A towering obelisk in a small Ontario town. A statue in British Columbia. An old railcar on display at a museum in Québec. A crumbling Halifax mansion. The name of a city in Saskatchewan.

We recently paid a visit to one of those memorials. You’ll find an elegant mausoleum in one of Toronto’s oldest graveyards, Mount Pleasant Cemetery. It’s a quiet building; we were the only living people there. Long corridors are filled with rows upon rows of the dead. And there, at the end of one of them, you’ll find the crypt of Mary Fortune — one of more than two thousand people who were on board the Titanic that dreadful night.

The Fortunes were a well-named family: they made a fortune in Manitoba real estate. And in 1912, they left Winnipeg for a grand tour of Europe. It was supposed to be a happy occasion, but there was at least one ill omen. During a visit to Cairo, a fortune teller gave one of Mary’s daughters a chilling warning: “You are in danger every time you travel on the sea, for I see you adrift in an open boat. You will lose everything but your life.”

Not long after that, the Fortunes boarded the Titanic for their voyage home.

They were far from the only Canadians on board. There were thirty-four Canucks in total. Among them were some of the most famous names in the country.

Harry Molson was the inheritor of the Molson brewing empire and the former Mayor of Dorval, Québec. He’d been planning to take another ship home, but his friend Arthur Peuchen — a Toronto entrepreneur and a major in the Queen’s Own Rifles — convinced him to travel back together on the Titanic’s maiden voyage instead.

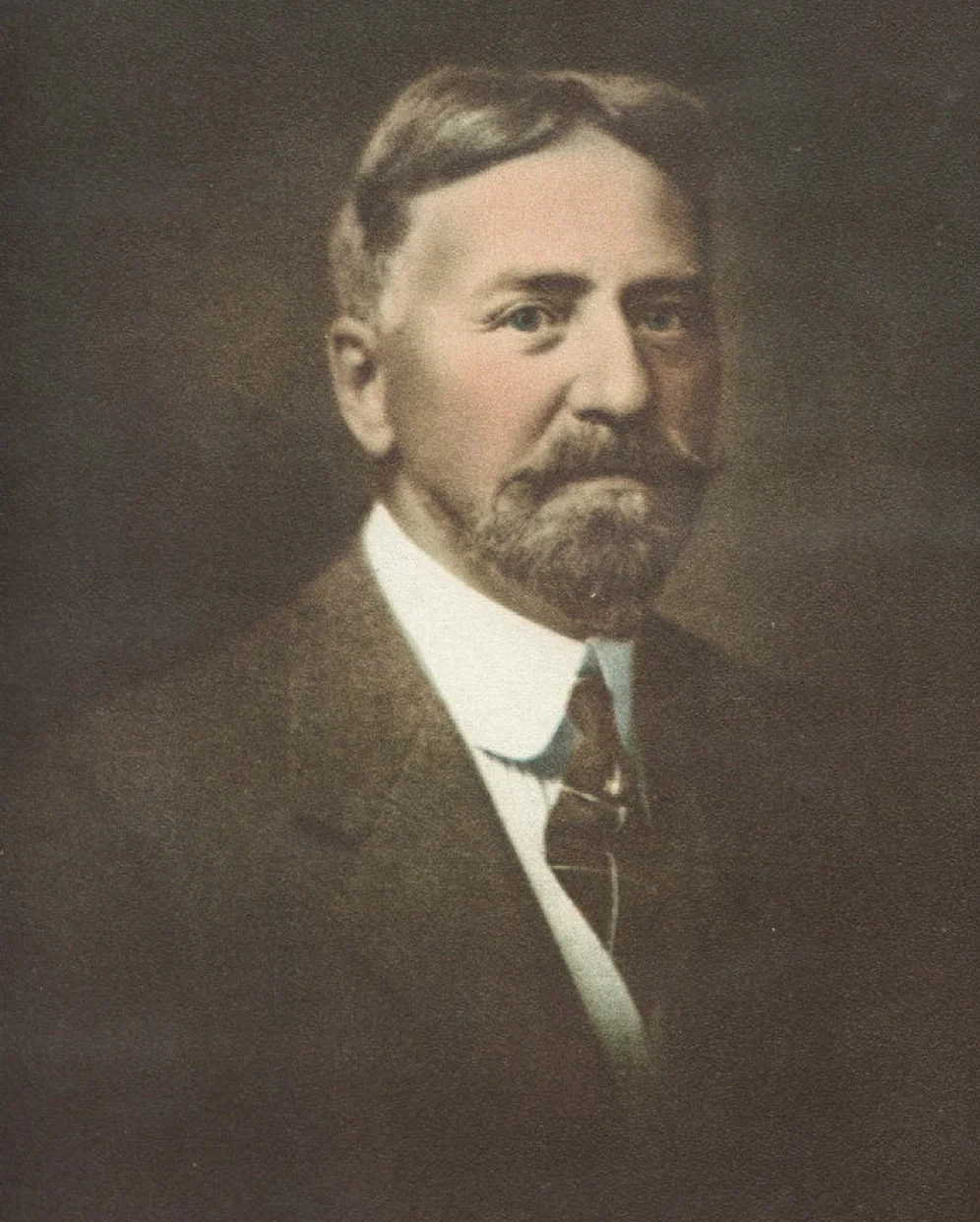

George Wright was a millionaire from Halifax, having made his fortune by publishing a wildly popular business directory. He was a shy man, so he stuck to his cabin for most of the voyage; no one could remember ever seeing him on deck. He hadn’t planned on taking the Titanic home either. He bought his ticket at the last minute. And just before he did, he mysteriously rewrote his will, leaving his mansion to the Halifax Local Council of Women — some say he was in love with one of the members. He would never see her again.

The Dicks were on their way home from their honeymoon. They were big in Calgary real estate. The Dick Business Block is standing in the Inglewood neighbourhood to this day. Bert was a bit grumpy on the trip because Vera was flirting with one of the young stewards. She was in awe of the sky on that final night, as the Titanic steamed across the Atlantic. "Even in Canada where we have clear nights,” she remembered, “I have never seen such a clear sky or stars so bright.”

Many of the Canadians on board knew each other. The Fortunes were old friends with the Allisons, who were one of the richest families on the entire ship — which is saying something on a boat filled with Guggenheims and Astors. Hudson Allison was one of Montreal’s most successful stock brokers. He and his wife Bess were heading home with their young children and some new servants they’d just hired in Scotland: a nurse, a chauffeur, a cook and a maid. Every evening, they had dinner with Harry Molson and Major Peuchen in the Titanic’s dining room. On that last night, they even let their little girl Loraine — just 2 years old — join them for a few minutes so she could see how beautiful the room was. It was especially regal for that final meal, tables adorned with flowers and fresh fruit. After dinner, they retired to the reception room to have coffee and listen to the orchestra.

Major Peuchen eventually headed off to the Smoking Lounge to hang out with some more Canadian friends. Three Winnipeg businessmen — they called them the Three Musketeers — had joined the Fortunes on a cruise down the Nile. When one of them, Hugo Ross, caught a terrible case of dysentery in Egypt, they decided to change their plans and head home early, joining the Fortunes on the Titanic. Ross was so sick he had to be carried aboard on a stretcher. Four days later, he was still bedridden, but the other two musketeers — Thomson Beattie and Thomas McCaffry, who were inseparable, shared a cabin, and may have been in love — joined Major Peuchen in the lounge. He stayed up chatting and puffing away with them until nearly 11:30pm.

Ten minutes later, he was back in his cabin getting undressed for bed. That’s when the iceberg hit.

"I felt as though a heavy wave had struck our ship,” he later remembered. “She quivered under it somewhat. I would simply have thought it was an unusual wave which had struck the boat; but knowing that it was a calm night and that it was an unusual thing to occur on a calm night, I immediately put on my overcoat and went up on deck.”

There, he found the starboard side littered with ice that had been carved off the iceberg as it scraped its way along the side of the ship. He was sure it was nothing serious. The Titanic, after all, was unsinkable.

A few minutes later, he ran into the most famous and powerful of all the Canadians on board: Charles Melville Hays. He was the president of the Grand Trunk Railway and the governor of McGill University as well as a couple of hospitals in Montreal. He was hurrying back to Canada to attend the opening of his brand new hotel: the Château Laurier in Ottawa. The owner of the Titanic had personally invited him to take the celebrated new ship home, and Hays brought his family, his secretary and a maid with him. Still, he wasn’t entirely impressed by ocean liners. Just an hour earlier, Hays had made a troubling prediction, “The time will come soon when this trend will be checked by some appalling disaster.”

But now, as Major Peuchen showed him the ice scattered across the deck and the great ship began to list to one side, Hays wasn’t worried. "You can't sink this boat," he told the Torontonian. "No matter what we've struck, she is good for eight or ten hours.”

Two hours later, Hays would be dead.

Mary Fortune was asleep when the iceberg hit, startled awake in her cabin by the force of the collision. When they learned what had happened, the Fortunes headed up toward the deck, toward the lifeboats, toward safety... but as they reached the stairway, they were stopped by some members of the crew. Only the women were allowed above, they explained; until all the women and children were safely evacuated, the men would have to stay below.

It was a death sentence.

The Fortunes had no idea how quickly the ship was sinking, how little time there was to escape. They didn’t even say a proper goodbye. As Mary and her daughters headed above, her husband Mark and their son Charles stayed behind. It was the last time they would ever see each other. Later that terrible night, Mark could be spotted on deck wearing his favourite bison fur coat from Winnipeg, happy it was keeping him warm in the cold April air. But soon, he and Charles would sink beneath the waves.

By the time the Fortune women reached their lifeboat, some passengers were already getting desperate. With only women and children being allowed into the lifeboats and the passengers’ widespread belief in the Titanic’s “unsinkable” reputation, many boats had already been lowered into the water nowhere near capacity. Increasingly desperate, some men tried to rush the crew loading the remaining boats. Mary watched as the officers struggled to hold the mob back, then fired their guns into the air as a warning — before turning that fire on the frightened men themselves.

Despite the chaos, Mary and two of her three daughters made it into a lifeboat without further incident. But as the boat readied to depart, Ethel Fortune still wasn’t there. She didn’t take the danger seriously at first; she returned to her cabin before a steward changed her mind.

The lifeboat was already being lowered over the side when Ethel finally arrived. By then, it was clear the Titanic was doomed; there was no time left to wait for her to climb in. She had to jump to make it, caught by the people already on board. And Ethel wasn’t the only one who risked her life to get inside that boat. A few jumped. A French woman missed and nearly fell to her death. A baby was thrown on board.

Finally, the lifeboat pulled away from the Titanic into the relative safety of the dark waves. As the Fortunes helped row the boat away from the massive sinking titan next to them, they could see the band playing on the deck of the ship, life preservers secured around their waists. The sound of ragtime tunes rang out in the night.

Nearly an hour later, they watched as the stern of the Titanic rose up into the night air. They could hear the screams. The lights flickered, went dark, and then the great ship split apart and disappeared beneath the waves.

The Titanic took more than 1,500 people down with it, including twenty Canadians — more than half of those who had been on board.

Harry Molson was last seen taking his shoes off, claiming he could see the lights of a ship on the horizon, about to make a desperate attempt to swim for it. They never found his body.

The shy millionaire, George Wright, was never seen at all. He seems to have stayed in his cabin right to the very end. He may have slept through the disaster. The old mansion he left to the Halifax Local Council of Women is still standing there today, though it’s showing its age as paint peels from its porch.

Hugo Ross, the Winnipeg musketeer suffering from dysentery, is also thought to have drowned in bed. Major Peuchen tried to rouse him after seeing the ice on deck. "Is that all?” Ross asked the major. “It will take more than an iceberg to get me out of my bed." And then he went straight back to sleep.

The second musketeer, Thomson Beattie, managed to get into the last available lifeboat. But it must have strayed too far from the site of the sinking; the rescue ships didn’t find it. It wasn’t discovered until a month later. Beattie’s corpse was found inside, still in his evening dress, along with two dead sailors, their hair bleached white by the sun. He died of exposure. Those who found him sewed him into a canvas bag, draped the Union Jack over his body, and buried him at sea.

The body of the third musketeers, his partner in life Thomas McCaffry, was found adrift in the water soon after the sinking.

Only one of the Allisons survived. When the time came for Bess Allison and her little girl Loraine to take a lifeboat, baby Trevor was missing. Bess refused to leave without her son and climbed back out onto the deck at the very last second. She couldn’t know that Trevor was already safe: his nurse had taken him in one of the other lifeboats. The baby’s mother, sister and father would all die on board. Only Hudson Allison’s body was ever recovered, but a towering obelisk has been erected to the family’s memory in Maple Ridge Cemetery in Chesterville, Ontario.

Charles Melville Hays helped his wife into a lifeboat, along with the other women in his party. They would all survive, but he, his son-in-law and his secretary stayed behind to die. His lifeless body was recovered from the water and buried in Montreal. Today, you’ll find the railcar that carried his corpse on display at the Canadian Railway Museum in Québec. His statue stands in Prince Rupert. The city of Melville, Saskatchewan is named after him. And some say his ghost still haunts the Château Laurier, the hotel he never did get to open.

The Dicks were saved by the same young steward Vera had been flirting with. The honeymooners didn’t feel the impact of the iceberg at all, but the steward came by their cabin just after midnight, made sure they put on their lifejackets, and then escorted them to a lifeboat. "We would have slept through the whole thing,” Bert admitted, “if the steward hadn't knocked on our door.” According to him, at the very moment he was hugging his wife goodbye, he was accidentally shoved into the lifeboat with her. It was already being lowered, too late for him to get out. He would face accusations of cowardice for the rest of his life.

So would Major Peuchen. As one of the lifeboats was being lowered, the crew member on board called out for another seaworthy man to join him — he was afraid he couldn’t manage the boat alone. Peuchen stepped forward: he owned a yacht in Toronto. He had to make a daring leap into the lowering boat, but made it safely. Thanks to that he survived... and was publicly reviled for the rest of his days. He, like Dick, was forever accused of having dressed in disguise as a woman to escape the sinking ship — even though eye witnesses defended him. Upon his return to Canada, he would be ostracized from Toronto society.

A man in the Fortunes’ lifeboat, on the other hand, had done exactly what the major was accused of. He wore a skirt, a bonnet, a blouse and a veil: a makeshift disguise to sneak aboard. He refused to give them his name.

The Fortunes and the rest of those in their crowded lifeboat waited all night for rescue to arrive. Dawn broke above the Atlantic before the Carpathia finally steamed into view. Theirs was the second-last lifeboat saved.

Mary Fortune never remarried — though she did live to see her grandson Gordon born; he would eventually go on to oversee the construction of the Avro Arrow. She moved to Toronto in her later years. That’s where she died, near St. Clair Avenue and Mount Pleasant Road, and she was laid to rest in the mausoleum at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

There, at Mary Fortune’s crypt, we found a note someone has left for her. It was placed there seven years ago, on the 100th anniversary of the sinking, to assure her that she — and her terrible loss — have not been forgotten, even after all these years.

Neither have the other Canadians who were on board the Titanic during that terrible spring night in 1912. You’ll find reminders all over our country. A towering obelisk in a small Ontario town. A statue in British Columbia. An old railcar on display at a museum in Québec. A crumbling Halifax mansion. The name of a city in Saskatchewan.

Want to read more stories like this? Become a champion of Canadiana on Patreon. Just a little monthly donation helps us to continue our hunt for the most incredible stories in Canadian history — and gets you access to exclusive content and other perks.

Have you checked out our award-winning series on YouTube? Find over 30 exciting and unique episodes here: https://www.youtube.com/canadiana